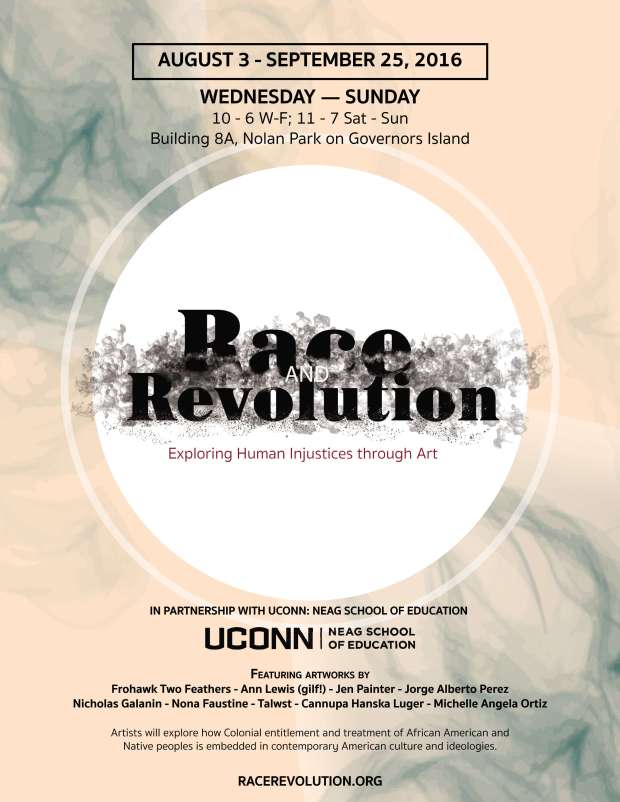

This has been a tough couple of weeks. Last summer, when a certain upcoming election was still wearing heavily on my mind, I decided I needed to better understand how the United States has, historically, created an “other”, that group of people who becomes the scapegoat in times of economic or physical turbulence. Where better to go than Tuskegee University, which holds the largest archives of lynchings in the United States? So here I am, at the end of a two-week research residency in Alabama, researching racial terrorism.

After 9/11 Newsweek published a title story “Why They Hate Us”. At they time I was teaching high school English. This cover photo and title so enraged me, so disgusted me by how irresponsible and inflammatory it was that I immediately bought a copy.

The image and its heading became a teaching tool for my persuasive writing unit: How does this magazine encourage xenophobia and Islamophobia? What responsibility do news sources have to present a perspective that does not incite fear and misunderstanding? Etc, etc. As I was researching newspaper sources on historical acts of domestic terrorism these past two weeks, these same questions occurred to me. How has media and how does media contribute to the perception of “other” as something to be feared and something to blame?

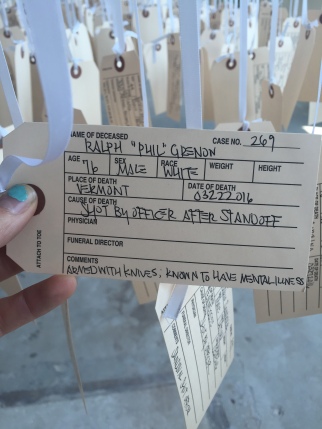

I spent time these past couple of weeks reading newspaper articles about lynchings written between 1899-1938, and counting the number of times the word “Negro” was used in place of “man”, “woman”, “person”, or “child”. In one article a young man was presented to the newspaper’s audience only as “negro” and “prisoner”. Might I add that the teenager in the story had not yet been found guilty of anything? Seldom was the person stated by his or her gender. Sometimes the word “boy” replaced “negro”, but these were rare occurrences.

Satire, an expressive tool I usually love, became a weapon when Northern papers reported on lynchings. I wonder if it is ever appropriate to use irony when addressing something so violent, toxic, and painful. Also, I am reminded of how satire used during the Election 2016 cycle wound up alienating voters who were wary of the political establishment. Could the same have been true during the years lynchings reached their peak?

Senator Bilbo from Mississippi said during the 1938 filibuster over the Anti-lynching Law that was being proposed, “Take out the 12,000,000 negroes and there will be a job for every white boy and every white girl.”

Why, in this country, does it constantly become one against the other? And how is this “other” determined? Why in a country that raises a torch in the spirit of Independence is it so terrifying to be a non-white male? Why, whenever someone challenges our thinking around the creation of “other” is there such a violent, repulsive backlash? Most importantly how can we learn to remain open to differences and things that challenge our perspectives and understandings of the world around us. Different is not wrong. Different has no judgment. It is just different.